Across the country, town centres are facing an identity crisis. The loss of major retail anchors — department stores and chain outlets that once drew the crowds — has created large, hollow buildings and even larger voids in civic life.

The absence of this activity seeps through the surrounding streets like dry rot: empty units mean lost revenue, lost confidence, and the slow erosion of community. What was once the social and economic heart of the town becomes its most fragile limb.

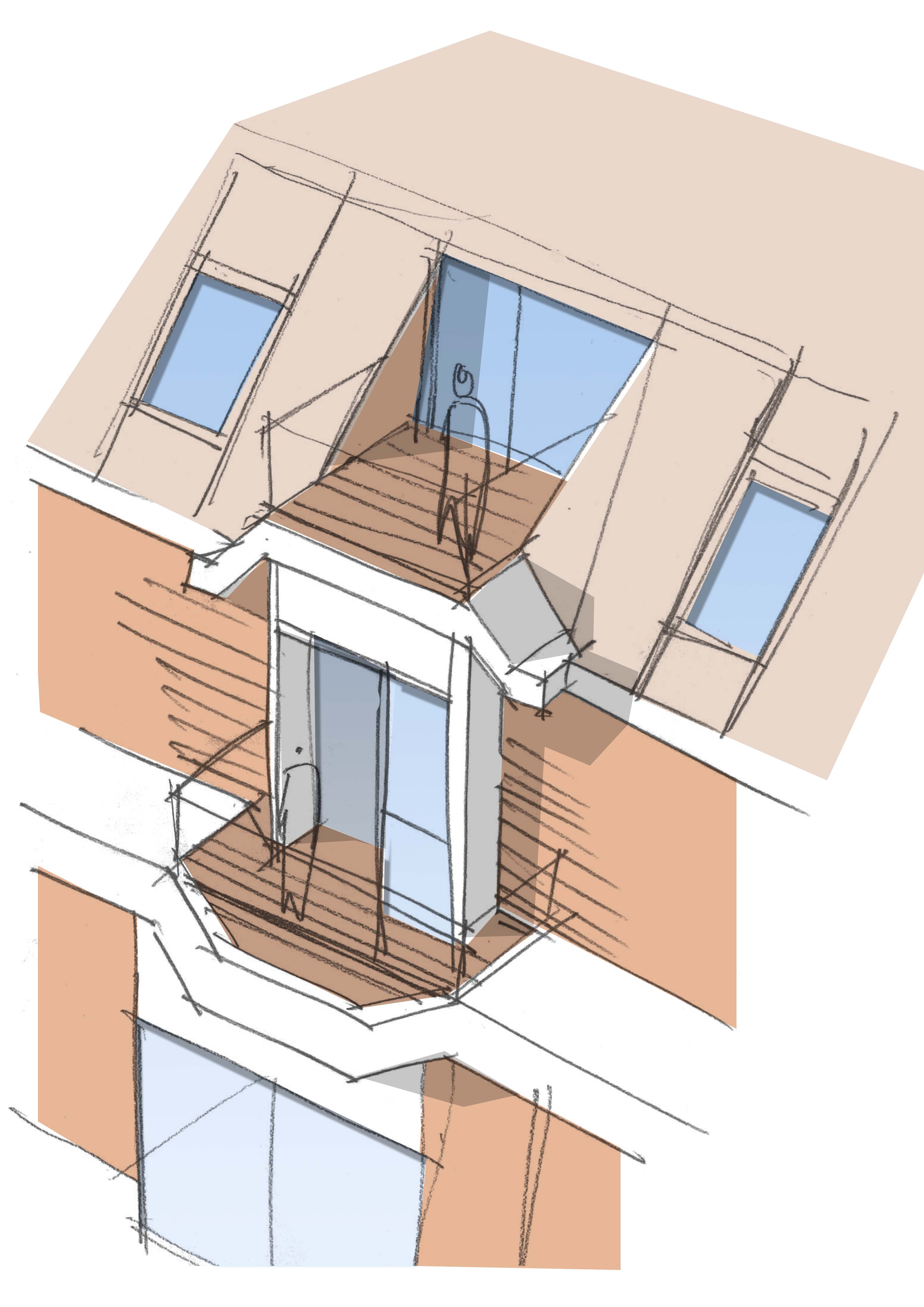

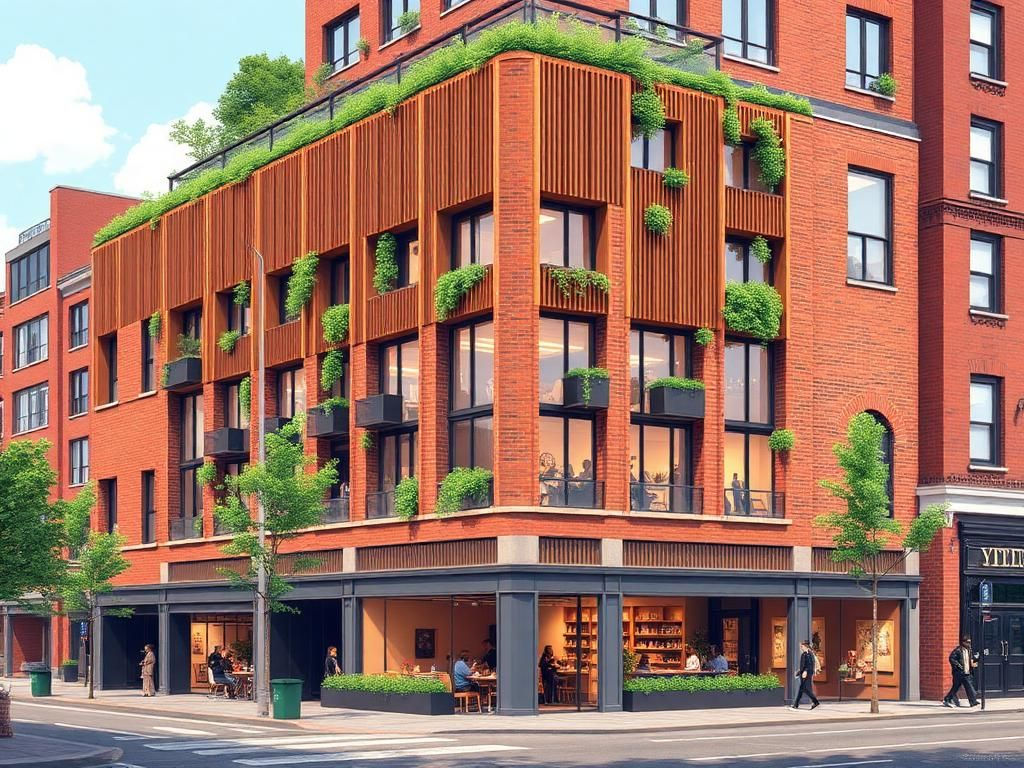

Revitalising these spaces is far from simple. Deep-plan commercial buildings are difficult to repurpose: they lack daylight, natural ventilation, and often rely on outdated servicing and access routes. Re-imagining them requires both boldness and restraint — cutting new lightwells, opening courtyards, reorganising circulation, and inserting greenery where once there was only floorplate. These are architectural challenges, but also social ones. The task is not only to make old buildings function again, but to make them belong again.

A successful high street now depends on diversity. Rather than a single retail model, we need a mosaic of uses: smaller independent shops, cafés, restaurants, nurseries, studios, gyms, and offices — and crucially, homes. Bringing residents into the centre reintroduces daily life and night-time presence, providing the constant pulse of footfall that retail alone can no longer sustain. Mixed-use is not a slogan but a survival strategy.

Yet physical change alone is not enough. What truly reanimates a town centre are the sociable spaces between — the places where people meet, linger, and connect. Entrances, courtyards, terraces, and shared gardens are not leftover spaces but essential infrastructure for civic life. They turn an address into a neighbourhood, a scheme into a community.

For landlords, developers and councils, this demands a new kind of stewardship — one that values long-term vitality over short-term yield. Buildings must be reconfigured, not simply re-let. Success depends on collaboration and care, and Stolon support them in this endeavour.

As architects we have a great responsibility to work creatively within complexity, to bring sociability and sustainability into the heart of our towns, and to show that even the most intractable buildings can be re-imagined as living parts of a shared future.